July 6, 2012 - 3:00am

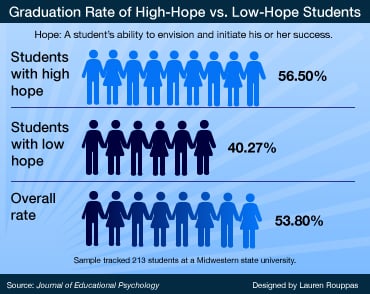

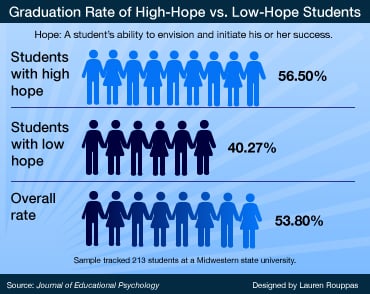

It doesn’t seem surprising that someone who can set goals, visualize paths to achieve them, and summon the motivation to start down those paths would be more likely to succeed than someone who can’t do those things. But measuring the potential effect of those characteristics – which together compose the characteristic of “hope” – is starting to become more clear. A growing (but still small) body of research is finding that students with high levels of hope get better grades and graduate at higher rates than those with lower levels, and that the presence of hope in a student is a better predictor of grades and class ranking than standardized test scores.

In one study at a Midwestern state university, hopeful students graduated at rates 16 percent higher than non-hopeful students. Another, at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, found that the presence of hope in first-semester law students there better predicted academic success than did ACT or LSAT scores. One study found that high-hope people experience less anxiety in general and in specific relation to test-taking situations. A longitudinal study of more than 100 students at two British universities found that hope was a better predictor of academic success than intelligence, personality or previous scholarly achievement.

Now, some of those same researchers are trying to figure out the next question: Can higher education use this to students’ advantage?

One longitudinal study showed long-term gains in life satisfaction and mental health from boosting hope in Portuguese middle school students. While studies of that sort are only just starting on college students, researchers are optimistic. (Optimism, mind you, is different from hope: the former is simply the belief that good things will happen; the latter deals with whether one can find a way to make good things happen.)

“We know we can enhance hope in a way that makes that bump stable, so it’s not just giving you a little hope bump and then two days later you’re bummed out again,” said Shane Lopez, research director at the Clifton Strengths Institute and a senior scientist in residence at Gallup. Lopez worked on the study of Portuguese students, and others. “It’s got a little bit of a stickiness to it, and it seems to be intuitive for students.”

How does one “enhance hope,” exactly? It is innate, to an extent, correlating with high optimism, self-esteem and perceived control and problem-solving abilities. But it can also be learned: train a student to visualize their goals, to see how they’ll achieve them, even when obstacles arise, and hope will follow, some experts say.

Some research on college students has found promising short-term results. In one study, 96 students at a California university who went through 90-minute “interventions” focused on increasing hope were more likely to have made progress toward their goals after a month.

During the hour-and-a-half session, researchers tested students’ initial hope levels, then spent time teaching them what hope is and how to think in more helpful ways. In a goal-mapping exercise, for instance, a student writes a goal – any goal – on the right-hand side of a piece of paper. Across the page, he or she writes three necessary steps to achieving that goal, along with one obstacle (and potential solution) that could occur with each step. Finally, students consider what it will take to stay motivated.

After that, students might go through a structured daydreaming exercise, in which they spend 20 minutes with their eyes closed, visualizing what they’ve just mapped out.

“The question that we’re asking is, 'Can you take people regardless of their natural level and raise it to a higher level?' and the answer seems to be 'yes.' A tentative 'yes,' ” said David B. Feldman, the Santa Clara University associate professor of counseling psychology who conducted the study. “They start to get excited about the goal, because they’ve seen

themselves accomplish it.”

Students who received the hope intervention were more likely than those who didn’t to show greater levels of hope immediately after the intervention, and reported making “significantly more progress” on their goals at the one-month follow-up.

Feldman admits that a 90-minute session isn’t likely to retain its effect after, say, four years of college. But if institutions did want to invest in this idea, he said, it could be as simple as hosting periodic workshops like the ones he did, having a website students can visit, or asking instructors to bring up the language of hope in their classes – not unlike the way faculty at religious colleges speak about spirituality.

“We live in a time where messages pervade our culture, in the U.S. and probably abroad, that no matter how hard you try, it’s not hard enough. People try hard and lose their jobs. People try hard and lose their houses. There is this sense that it’s no use to set goals, and people as a result lose their hope, their hope in their own power, in their ability to control their lives,” Feldman said, speculating that low hope is not unrelated to a steady increase in students’ use of counseling services. “I don’t think students are immune to this. How could they be? So I think we as educators are in a unique position to inspire them and give some of that hope back.”

That’s what Laura Hope, dean of instructional support, is trying to do at Chaffey College – and the beneficiaries aren’t whom you might think.

“I think this not only has the capacity to really improve the lives of students, but from what we’ve been hearing from the faculty, it’s really improved their lives as well,” Hope said. “They misread a lot of cues from students as disinterest or dislike, when in fact it was disengagement driven by fear. And I don’t think they understood that before.”

But Chaffey is going all-out with hope theory, sponsoring a summer “institute” in which the professors become the students, and are put in the hot seat as instructors call them out on not doing homework, predict that many will drop out, and are neglected when they ask questions or need help. They get a “low-hope syllabus” packed with challenging assignments but with no advice or offers to help.

Switching over to the high-hope syllabus and talk, the effect on morale becomes clear.

“It’s an interesting dialogue for the faculty to have because it helps them to reflect on the things that they’re consciously or unconsciously doing,” Hope said. “Teaching strategy, I think just like student strategy, is not even so much about particular tools as it is a level of self-awareness.”

So, now, faculty members are essentially acting out the institute in their own classrooms, with professors and academic counselors are learning to – much to Feldman’s delight – speak in more hopeful language. (Meaning that a comment from a student or professor with a “determinism about failure” – say, “I was never very good at this” or “I knew I wouldn’t do well on this test” might prompt a response of “Well, why not?” or “let’s talk about what you need to do to do better next time.” The student should see him- or herself as the agent of success or failure, Hope said, distinguishing the practice from “cheerleading.”)

In the meantime, Chaffey is starting to test hope levels in all incoming freshmen for a longitudinal study to help identify which students might need interventions, and when.

The new LASSO Center at Oklahoma State University is exploring similar ideas related to self-efficacy: teaching students (in this case, at-risk ones) that it’s not “just them” having trouble, that they do have the ability to overcome, and they just need to develop the study skills and attitude to do it.

“What universities traditionally do is a mistake. Instead of developing for [students’] sense of, what’s your purpose in life and how are you going to achieve it, they just develop this big knowledge base…. The reason you lose a lot of kids is they kind of give up hope on themselves,” said Robert J. Sternberg, a celebrated psychologist and provost and senior vice president at Oklahoma State. “For me, the whole university is based around this notion that we’re not just trying to teach kids a lot of facts and how to analyze those facts, but how to create meaningful lives.”

Research into hope and academic performance really only started up a couple of decades ago. And while work at Chaffey, Oklahoma State and elsewhere demonstrate there is a market for applying it practically, the idea clearly has yet to catch on more broadly.

“By and large, universities are hesitant to try something new,” Lopez said. “It takes high-hope leaders to invest in something like this and…. not all of them are the most creative folks. So it’s slow on the uptake.”

In one study at a Midwestern state university, hopeful students graduated at rates 16 percent higher than non-hopeful students. Another, at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, found that the presence of hope in first-semester law students there better predicted academic success than did ACT or LSAT scores. One study found that high-hope people experience less anxiety in general and in specific relation to test-taking situations. A longitudinal study of more than 100 students at two British universities found that hope was a better predictor of academic success than intelligence, personality or previous scholarly achievement.

Now, some of those same researchers are trying to figure out the next question: Can higher education use this to students’ advantage?

One longitudinal study showed long-term gains in life satisfaction and mental health from boosting hope in Portuguese middle school students. While studies of that sort are only just starting on college students, researchers are optimistic. (Optimism, mind you, is different from hope: the former is simply the belief that good things will happen; the latter deals with whether one can find a way to make good things happen.)

“We know we can enhance hope in a way that makes that bump stable, so it’s not just giving you a little hope bump and then two days later you’re bummed out again,” said Shane Lopez, research director at the Clifton Strengths Institute and a senior scientist in residence at Gallup. Lopez worked on the study of Portuguese students, and others. “It’s got a little bit of a stickiness to it, and it seems to be intuitive for students.”

How does one “enhance hope,” exactly? It is innate, to an extent, correlating with high optimism, self-esteem and perceived control and problem-solving abilities. But it can also be learned: train a student to visualize their goals, to see how they’ll achieve them, even when obstacles arise, and hope will follow, some experts say.

Some research on college students has found promising short-term results. In one study, 96 students at a California university who went through 90-minute “interventions” focused on increasing hope were more likely to have made progress toward their goals after a month.

During the hour-and-a-half session, researchers tested students’ initial hope levels, then spent time teaching them what hope is and how to think in more helpful ways. In a goal-mapping exercise, for instance, a student writes a goal – any goal – on the right-hand side of a piece of paper. Across the page, he or she writes three necessary steps to achieving that goal, along with one obstacle (and potential solution) that could occur with each step. Finally, students consider what it will take to stay motivated.

After that, students might go through a structured daydreaming exercise, in which they spend 20 minutes with their eyes closed, visualizing what they’ve just mapped out.

“The question that we’re asking is, 'Can you take people regardless of their natural level and raise it to a higher level?' and the answer seems to be 'yes.' A tentative 'yes,' ” said David B. Feldman, the Santa Clara University associate professor of counseling psychology who conducted the study. “They start to get excited about the goal, because they’ve seen

themselves accomplish it.”

Students who received the hope intervention were more likely than those who didn’t to show greater levels of hope immediately after the intervention, and reported making “significantly more progress” on their goals at the one-month follow-up.

Feldman admits that a 90-minute session isn’t likely to retain its effect after, say, four years of college. But if institutions did want to invest in this idea, he said, it could be as simple as hosting periodic workshops like the ones he did, having a website students can visit, or asking instructors to bring up the language of hope in their classes – not unlike the way faculty at religious colleges speak about spirituality.

“We live in a time where messages pervade our culture, in the U.S. and probably abroad, that no matter how hard you try, it’s not hard enough. People try hard and lose their jobs. People try hard and lose their houses. There is this sense that it’s no use to set goals, and people as a result lose their hope, their hope in their own power, in their ability to control their lives,” Feldman said, speculating that low hope is not unrelated to a steady increase in students’ use of counseling services. “I don’t think students are immune to this. How could they be? So I think we as educators are in a unique position to inspire them and give some of that hope back.”

That’s what Laura Hope, dean of instructional support, is trying to do at Chaffey College – and the beneficiaries aren’t whom you might think.

“I think this not only has the capacity to really improve the lives of students, but from what we’ve been hearing from the faculty, it’s really improved their lives as well,” Hope said. “They misread a lot of cues from students as disinterest or dislike, when in fact it was disengagement driven by fear. And I don’t think they understood that before.”

But Chaffey is going all-out with hope theory, sponsoring a summer “institute” in which the professors become the students, and are put in the hot seat as instructors call them out on not doing homework, predict that many will drop out, and are neglected when they ask questions or need help. They get a “low-hope syllabus” packed with challenging assignments but with no advice or offers to help.

Switching over to the high-hope syllabus and talk, the effect on morale becomes clear.

“It’s an interesting dialogue for the faculty to have because it helps them to reflect on the things that they’re consciously or unconsciously doing,” Hope said. “Teaching strategy, I think just like student strategy, is not even so much about particular tools as it is a level of self-awareness.”

So, now, faculty members are essentially acting out the institute in their own classrooms, with professors and academic counselors are learning to – much to Feldman’s delight – speak in more hopeful language. (Meaning that a comment from a student or professor with a “determinism about failure” – say, “I was never very good at this” or “I knew I wouldn’t do well on this test” might prompt a response of “Well, why not?” or “let’s talk about what you need to do to do better next time.” The student should see him- or herself as the agent of success or failure, Hope said, distinguishing the practice from “cheerleading.”)

In the meantime, Chaffey is starting to test hope levels in all incoming freshmen for a longitudinal study to help identify which students might need interventions, and when.

The new LASSO Center at Oklahoma State University is exploring similar ideas related to self-efficacy: teaching students (in this case, at-risk ones) that it’s not “just them” having trouble, that they do have the ability to overcome, and they just need to develop the study skills and attitude to do it.

“What universities traditionally do is a mistake. Instead of developing for [students’] sense of, what’s your purpose in life and how are you going to achieve it, they just develop this big knowledge base…. The reason you lose a lot of kids is they kind of give up hope on themselves,” said Robert J. Sternberg, a celebrated psychologist and provost and senior vice president at Oklahoma State. “For me, the whole university is based around this notion that we’re not just trying to teach kids a lot of facts and how to analyze those facts, but how to create meaningful lives.”

Research into hope and academic performance really only started up a couple of decades ago. And while work at Chaffey, Oklahoma State and elsewhere demonstrate there is a market for applying it practically, the idea clearly has yet to catch on more broadly.

“By and large, universities are hesitant to try something new,” Lopez said. “It takes high-hope leaders to invest in something like this and…. not all of them are the most creative folks. So it’s slow on the uptake.”

Read more: http://www.insidehighered.com/news/2012/07/06/researchers-apply-hope-theory-boost-college-student-success#ixzz2095Y9t8B

Inside Higher Ed

No comments:

Post a Comment